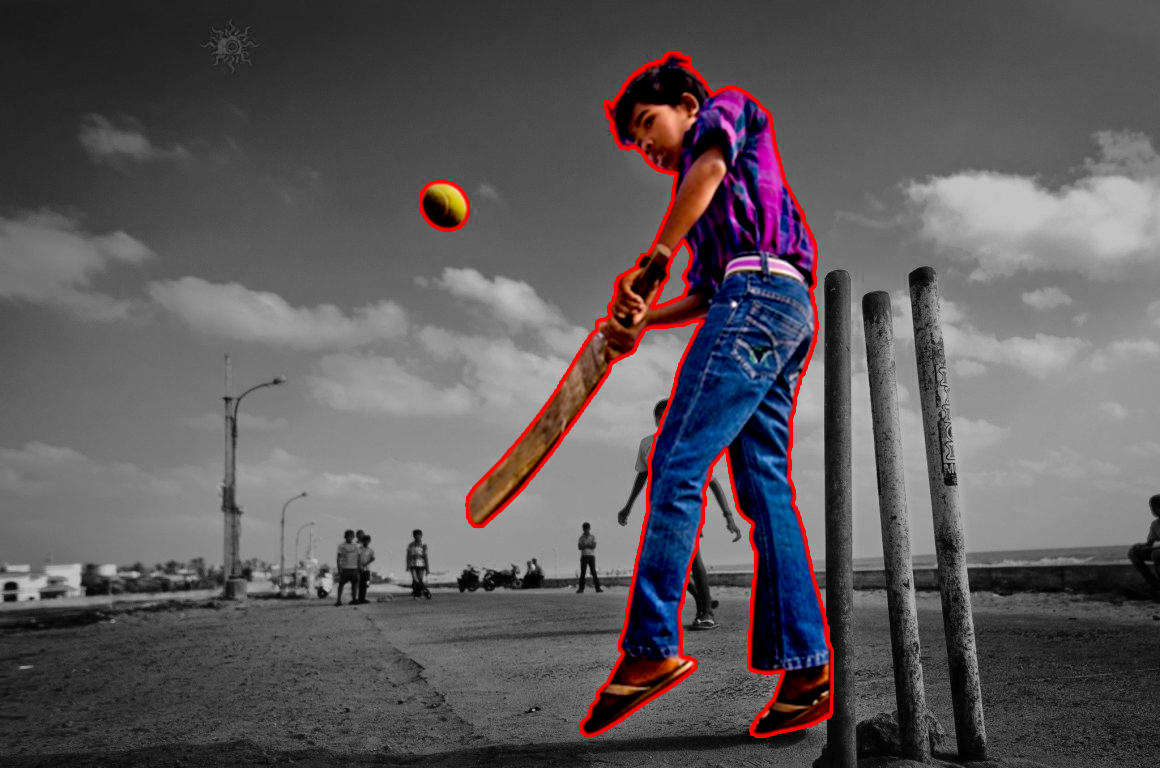

What do these words mean? Little Ansh did not have the foggiest idea. Two young, bearded men in kurtas, stood across the road. The midday sun was out and Ansh, a 5-year-old with beady eyes and curly hair, was standing in his familiar playground. When they came close, he heard the one without camera muttering these lines.

“Violence is a culture found in playgrounds. Cities fail to let their children breath.”

It is a routine day for Ansh. Up by 5:00 AM, out of his house by 5:30 AM with his mother for a 2-hour train journey to her place of work, while father stayed in bed till the sun was down. He did not have a job, he was waiting for the perfect position, he’d say. His mother on the other hand must be quite good at what she did, her workspace came with a large playground, entirely for him. A large heap of golden sand, that glittered under the Delhi summer sun, and a stack of red bricks conveniently placed. There were towels, shovels, head pans, bucks of varied colours and a bright blue drum of water. She was a daily wage labourer; mixed cement, sand, and gravel to arrive at soft but sturdy concrete, and reported to stern and shoddy - Mr. Yadav. Ansh’s mother was a construction worker.

Mr. Yadav reminded Ansh of his father but he was up and about during the day. Though he did not seem to do much through the length of the day.

Ansh did not take much notice of the man as he went about his daily activities in his place of play. First, was a round of brick smashing. As the name suggests, he took the biggest brick he could lift and smashed it on the ground. Then took the largest piece from the remains and smashed that on the ground. The round was over when he decided, as there was always a largest piece on the floor. The game gave him full control. One time, a colleague of Ansh’s mother – Mr. Prasad proposed another dimension to the game. Instead of smashing the largest piece on the ground, you smash the largest piece on the largest ant you can spot. Ansh tried this version for a couple of days. Until, he smashed the largest piece on his largest toe and had to spend the next week at home with his snoring father. He did not like his father, he did not like Mr. Prasad, and he particularly disliked his version of the game.

Luckily, there were other games to play. He drew lines in the sand, counted the bricks, picked out the hottest and coldest stone chip from the large heap, and observed his mother as she toiled away. It fascinated him – her work. Carrying a head pan of sand, carrying cement, followed by stone chips. When he thought about it, it seemed to be a monotonous sequence of events every day. But to him each day was different. Each day, he was sitting in a different place, his mother surrounded by different people, and the number of largest pieces he’d smashed, different.

But for Ansh, the journey to his mother’s place of work was always most exciting.

First, before boarding the train, they had to cross the street with thirteen puddles. While he jumped over them with joy, his mother struggled – rolling her ankle or dipping the edge of her sari in the muddy water.

Next, after getting off the train, came the shop where they would buy bananas. But the footpath to reach the shop was raised – one could either take big step or follow along a broken slope next to it. Ansh’s hand was held extra tightly here, for his step was too small for the height of the footpath and the slope too sandy for his slippers. It was his second task of the day – overcome this barrier, and he was rewarded with a banana.

Then came a road crossing on which cars, buses and rickshaws went fast. They would have never been able to cross unless a kind driver slowed down. Coincidentally, every driver that slowed down also peeked into a mandir on the other side, joined their hands and shut their eyes. That is when his mother and him would rush across.

Three checkpoints conquered till they reached their destination for the day.

Nowadays, more men were coming with the cameras at his play site; taking more pictures and uttering sentences Ansh couldn’t comprehend. They never seemed to do anything. Again, that reminded Ansh of his father. He too would talk about doing things but not do any. Ansh had decided he wants to be like his mother when he grew up

The routine did not last for long; the men stopped showing up altogether. So did Ansh’s visits to his playground.

On a rainy day, in his mother’s next place of work, where all he had to himself was a blue shed and two dogs.

‘They bought me ice cream and but did not play with me. They asked my name but never told me theirs. They asked where I stayed but never told me where they came from. A few weeks past, I saw them less. The building grew, my playground shrunk. Soon, I found out where they lived. The very same site that my mother built. Perhaps, they knew a home for them meant no playground for me.’

References

1. Jussawala, Adil. “Bomb-site” Land’s End. Writers Workshop, 1962, pp 96

About the Author

Taha Mama is a student at Jindal School of Art & Architecture, Sonipat. He was part of ITCN capacity building programme as an academic intern in summer of 2022.

Add new comment